J Res Clin Med. 12:24.

doi: 10.34172/jrcm.34594

Original Article

Elder abuse among older persons in a local government area in southwest Nigeria: A cross-sectional study

Oladele Ademola Atoyebi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Eyitayo Ebenezer Emmanuel Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 2

Tope Michael Ipinnimo Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1, *

David Sylvanus Ekpo Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Kehinde Hassan Agunbiade Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Taofeek Adedayo Sanni Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Olufunmilayo Elizabeth Atoyebi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 3

Paul Oladapo Ajayi Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Author information:

1Department of Community Medicine, Federal Teaching Hospital, P.M.B 201, Ido-Ekiti, Nigeria

2Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria

3Department of Ophthalmology, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital Complex, Ile-Ife, Nigeria

Abstract

Introduction:

Elder abuse is a major but subtle social problem affecting millions of older adults globally. Nigeria, a developing nation with about 4% of her 200000000 population being older persons is not left out. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and correlates of elder abuse in Oye Ekiti Local Government, Ekiti State, Nigeria.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study of 275 consenting seniors residing in households located in Oye Ekiti Local Government Area was conducted. A correlational matrix was constructed using Pearson correlational coefficients to determine the association between the various sociodemographic characteristics and abuse.

Results:

Most respondents were males (62.5%) and aged 65 to 74 years (66.9%). Financial abuse was the most prevalent form of abuse (13.8%). The prevalence of abuse increased with age and 15.8% of those aged 65–74 years had suffered a form of abuse compared to (37.5%) aged 85 years and above (OR=3.21, CI: 1.28 – 8.02, P=0.001). Low income and poor formal education were more associated with abuse.

Conclusion:

Targeted measures and policies should be employed against elder abuse, especially among the oldest old.

Keywords: Abuse, Elderly, Nigeria, Older persons

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Authors.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Funding Statement

No funds, grants, or other support was received for this study.

Introduction

Elder abuse is a huge but easily overlooked problem in the society. Despite its significantly distressing effects on the victims, it is often given little or no attention for mitigation and possible litigation of abusers. The World Health Organization (WHO) has described elder abuse as ‘a single or repeated act or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person’.1 Also described as a knowing, intentional, or negligent act by a caregiver or any other person that causes harm or serious risk of harm to a vulnerable adult usually above 65 years of age, it can be in the form of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, financial exploitation, neglect or abandonment.2 No single sign necessarily indicates abuse and suffering is often in silence. Abuse is a major social problem affecting millions of older adults across the globe. It is made worse by the fact that older persons are less likely to report abuse.2,3 Victims might also protect abusers or be too frightened or disabled to talk about the abuse.

A systematic review of articles on elder abuse in community settings from inception to 2015 showed that 1 in 6 older adults (15.7%) were victims of abuse.4 Additionally, 64.2% of staff in another systematic review admitted to elder abuse in an institutional setting.5 However, only a small fraction of this was reported to the appropriate authorities. Abuse can occur in institutional settings like hospitals and care homes by carers as well as in domestic/private household settings by a family member or an intimate partner.6 A report submitted to the UK Parliament revealed that 67% of abuse was traceable to victims’ homes, 12% to nursing homes, 10% to residential care, 5% in hospitals, 4% occurred in sheltered housing and 2% in other locations.7 Likewise, findings from research in Israel showed that 52% of carers reported being involved in abuse.8

The health consequences of elder abuse are very significant and could reduce the quality of life of older persons by causing a decline in functional abilities, increased stress, depression, dementia, malnutrition, and eventually, early death. The risk of death for victims is three times higher than for non-victims. Possible signs of abuse in older persons include bruises, fractures, fear, depression, loss of sleep, unexplained change in behavior, unusual activity in bank accounts or a sudden drop in finances, unkempt and dirty appearance, and sexually transmitted diseases.9

The risk factors for abuse usually involve an interaction of multiple victim or carer factors. Circumstances such as memory or communication defect, fear of loneliness or shame, substance use by the abuser, poverty, inadequate support system, unemployment, family history of domestic violence, inexperienced or unwilling caregiver, poor implementation of laws, policies, and poor supervision, mental illness in carer or victim, poor family relationship, as well as social isolation are related to elder abuse.1,10 In addition, previous abuse is closely linked to the likelihood of continuity of domestic abuse (lifespan approach described by Dixon and colleagues11) and is said to be involved in 64% of cases by Akpan and Umobong.12

In Nigeria, a study from Akwa Ibom identified emotional abuse as the most prevalent form of elder abuse.13 In about half of the cases, mistreatment was by a spouse/partner (51%), while another family member, a care worker, and a close friend were responsible for 49%, 13%, and 5% respectively.6 An establishment of trust has been found to exist in most instances of elder abuse.14 Another study from Northern Nigeria found no case of physical, financial, or psychological abuse but reported neglect among one-third of its participants.15 Along the same line, various and different factors have been associated with elder abuse by other research conducted in the country. In Osun, Nigeria, only religious affiliation was shown to have any significant contribution to elder abuse.16

While focus had been drawn to the phenomenon of elder abuse in the developed world as far back as the 1980s, it is still much not discussed in developing countries particularly in Nigeria.17 Although some research has been done on elder abuse in some Nigerian communities, there is room to explore abuse among older adults in other populations. About 4% of the Nigerian population is aged 65 years and above according to the national population census report this population is expected to increase.18 As at the time of this research, there is no policy addressing elder abuse in Nigeria. Thus, there is a need to initiate further research into the prevalence and correlates of elder abuse to set the base for adequate national and international data collection which would assist in the development of appropriate policy to mitigate the problem of elder abuse in developing countries. This study intends to explore the pattern of elder abuse among older persons in the Oye Ekiti Local Government Area. It will add to the existing knowledge and literature on the subject. It is expected that this will help encourage further research and data collection that would help in the formulation of guided policies and solutions.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional analytical study carried out in a Local Government Area in South West Nigeria. For this study, we defined the elderly as anyone aged 65 and above.19 The study population consisted of persons aged 65 years and above residing in households located in the Oye Ekiti Local Government who were able and willing to respond to the questions and participate in the research procedures were included in the study. Older persons who were critically ill, or in a hospitalized setting were excluded as well as those who did not give consent for participation.

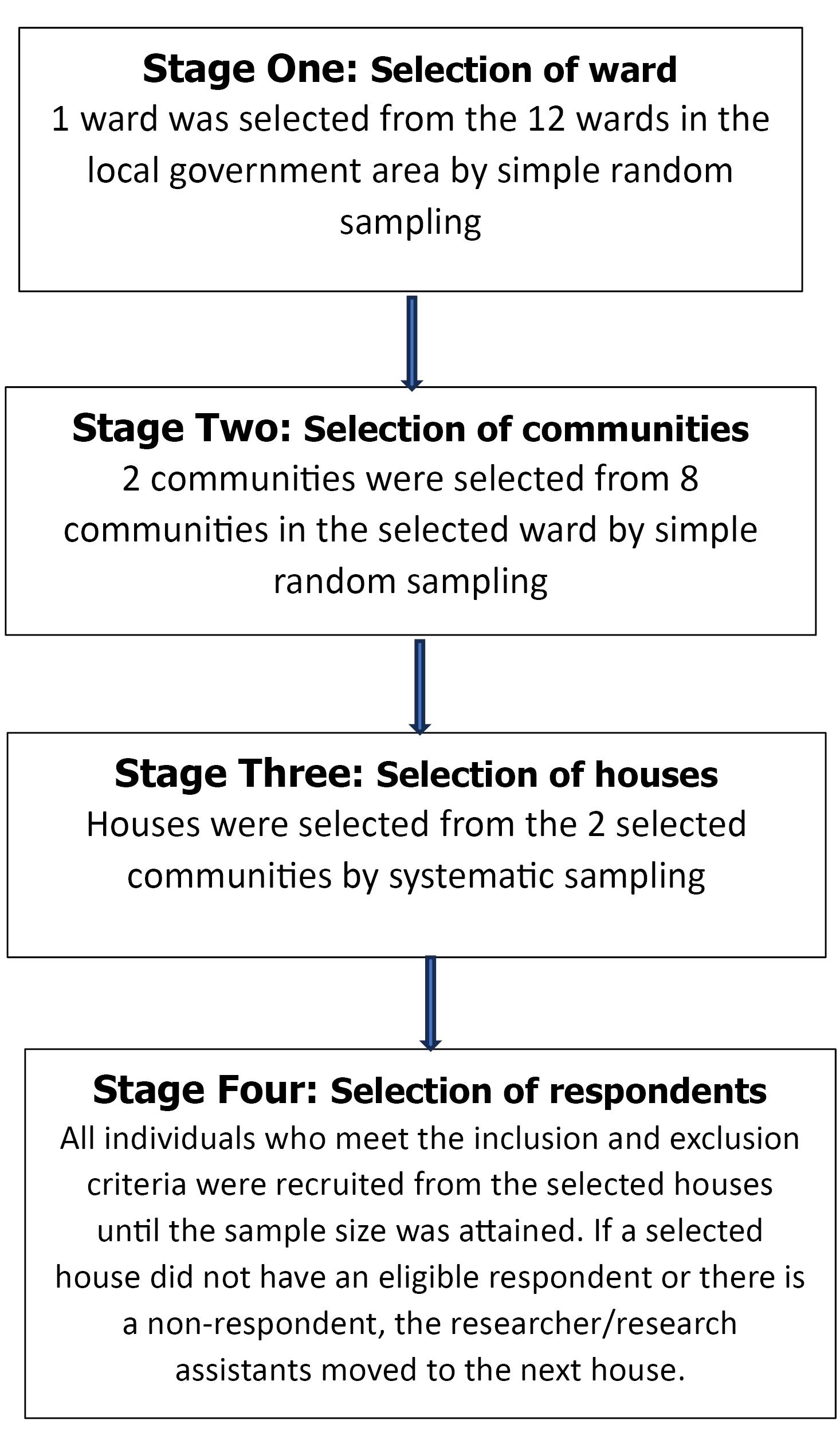

A total of 275 respondents were included in the study after adding 10% to the calculated sample size to cover for non-response. The sample size was estimated using the formula n = (Z2P( 1 - P ) )/ d2 Where n is the sample size, Z is the statistic corresponding to level of confidence and P is the expected prevalence that was obtained from similar study.11 Multi Stage Sampling Techniques was used to select the respondents in this study. Multi-stage sampling technique was used to select the respondents in this study. Oye-Ekiti LGA is divided into 12 wards. The following stages of the sampling technique were used (Figure 1):

-

Stage 1: One ward was selected from the twelve wards using a simple random sampling technique by balloting. This selected ward had eight communities.

-

Stage 2: In stage 2, two communities were selected by simple random sampling technique by balloting method without replacement.

-

Stage 3: In each of the communities selected in stage two, proportionate allocation of calculated sample size was used to apportion the number of respondents to be sampled. House numbering was done in each community. Systematic random sampling was used: the first house was selected by simple random sampling and subsequent houses to be involved in the study were selected based on the sampling ratio.

-

Stage 4: In each house selected in Stage 3, total sampling was used and all those who met the study criteria were recruited for this study until the sample size was attained. If a selected house did not have an eligible respondent, the researcher/research assistants moved to the next house. Also, non-respondents were replaced by moving to the next house to reduce non-response bias. The reason for the non-responses was a lack of consent by a few potential respondents.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the selection of eligible respondents

.

Flow diagram showing the selection of eligible respondents

An interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from the Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale (VASS) was used for this research.20 This questionnaire has been validated across countries and cross-culturally and it is shown to have adaptability to various populations20 so we did not validate it for use in this study. Informed consent was obtained from each respondent before the study. The questionnaire elicited information on the respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, economic characteristics, abuse, and support. Physical abuse was defined as being restrained, hit, shoved, kicked, or burned; psychological/emotional abuse as humiliation, controlling attitudes, and threats; sexual abuse as inappropriate touching or rape; financial abuse as stealing of money belonging to an older person or taking over their property without consent; neglect as mistreatment from abandonment; and verbal abuse as negative defining statement or reviling. In addition, emotional support was defined as being able to find companionship, empathy, love, and trust if and when needed; physical support as being able to get assistance for mobility and other activities of daily living if and when needed; and financial support as being able to get money and other resources for daily living if and when needed. Multiple responses were allowed on support and forms of abuse suffered by the respondent.

Data collation and editing were done manually to detect omissions and to ensure uniform coding. The data were entered into a computer and analysis was done using SPSS version 21. The income was categorized ( < 20 000 Naira and 20 000 Naira and above) based on the minimum wage cutoff as at the time of study. Frequency tables and cross-tabulations were generated as necessary. The chi-square test was used to determine the statistical significance of observed differences in cross-tabulated variables, odds ratio and confidence interval were also presented. P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido-Ekiti. The welfare of all research participants was ensured throughout this research. The respondents were identified by serial numbers on the questionnaires which were stored in a locked cabinet. The computer used for data entry and analysis was also locked with a password known only to the researcher.

Results

A total of 275 elderly were studied comprising 172 (62.5%) males and 103 (37.5%) females (Table 1) with the majority (66.9%) between the ages of 65 to 74 years. More than half of the respondents (72.7%) earned below 20 000 Naira each month while 76.4% spent less than 20 000 Naira per month. More than a third of the respondents (38.5%) owned their houses and 200 (72.8%) were married. Furthermore, almost half of the research participants (41.8%) had no formal education while about half (49.1%) had primary education as the highest educational level.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

|

Characteristic

|

Category

|

Frequency (N=275)

|

(%)

|

| Age interval (years) |

65–74 |

184 |

66.9 |

| 75–84 |

67 |

24.4 |

| 85 and above |

24 |

8.7 |

| Gender |

Male |

172 |

62.5 |

| Female |

103 |

37.5 |

| Income |

< 20 000 Naira |

200 |

72.7 |

| 20 000 Naira and above |

75 |

27.3 |

| Expenditure |

< 20 000 Naira |

210 |

76.4 |

| 20 000 Naira and above |

65 |

23.6 |

| Tenure of house |

Owned |

106 |

38.5 |

| Family house |

69 |

25.1 |

| Owned by sibling |

23 |

8.4 |

| Rented |

77 |

28.0 |

| Education level |

No formal education |

115 |

41.8 |

| Primary |

135 |

49.1 |

| Secondary |

20 |

7.3 |

| Post-secondary |

5 |

1.8 |

| Occupation |

Trader |

73 |

26.5 |

| Farmer |

157 |

57.2 |

| Artisan/Technician |

10 |

3.6 |

| Civil servant |

5 |

1.8 |

| Retired |

30 |

10.9 |

| Marital status |

Single |

25 |

9.1 |

| Married |

200 |

72.8 |

| Divorced |

10 |

3.6 |

| Widowed |

40 |

14.5 |

Financial abuse was the most prevalent form of abuse with 13.8% of respondents having experienced it (Table 2) while physical and verbal forms of abuse were the least common with a prevalence of 1.8% each among respondents.

Table 2.

Prevalence of different forms of abuse

|

Abuse (N=275)

|

No (%)

|

Yes (%)

|

| Physical |

270 (98.2) |

5 (1.8) |

| Psychological/ Emotional |

261 (94.9) |

14 (5.1) |

| Sexual |

266 (96.7) |

9 (3.3) |

| Financial |

237 (86.2) |

38 (13.8) |

| Neglect |

261 (94.9) |

14 (5.1) |

| Verbal |

270 (98.2) |

5 (1.8) |

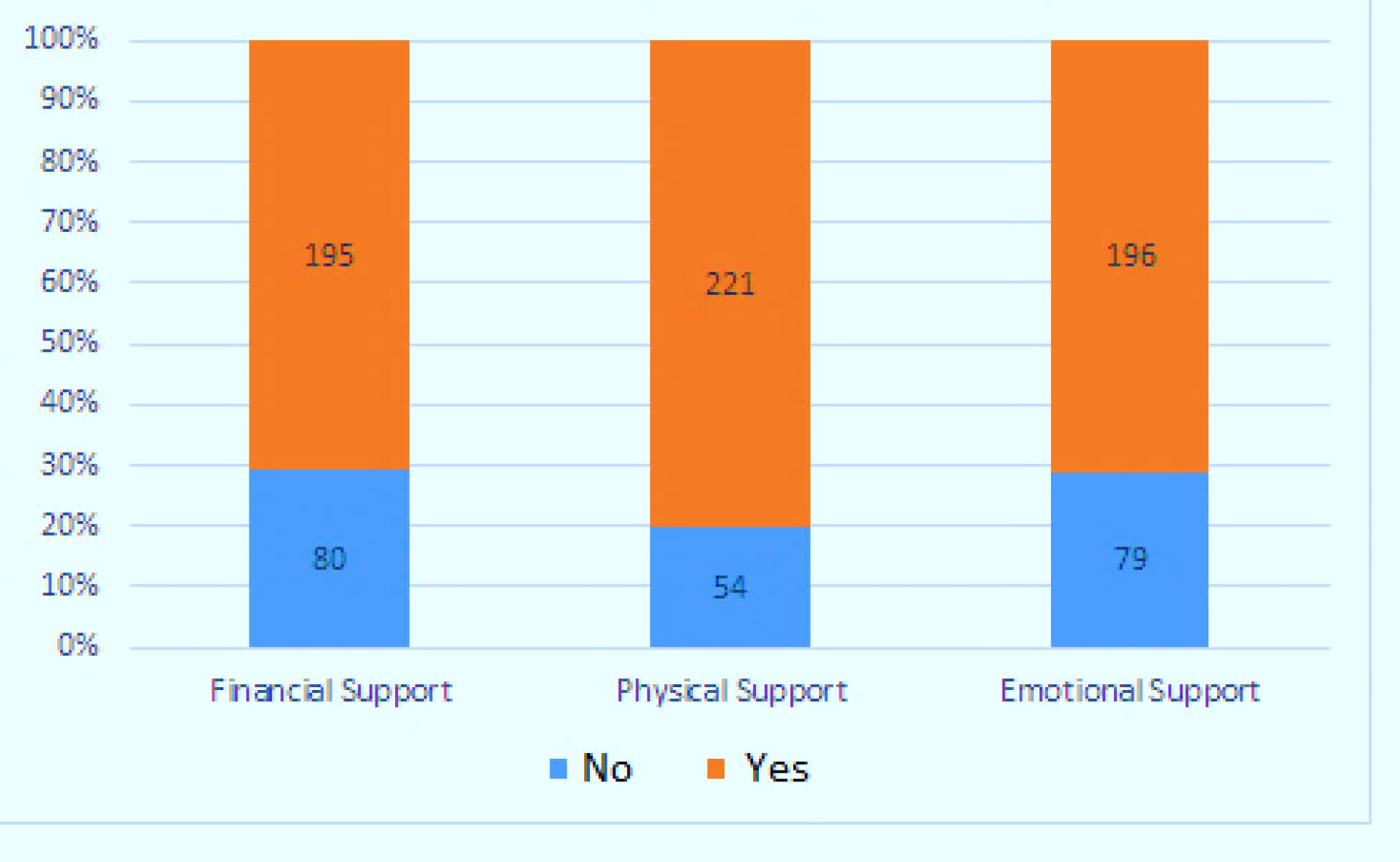

More than 70% of the respondents had financial, physical, and emotional support from relatives and friends (Figure 2). However, physical support was the most prevalent form (80.4%) while financial support was the least (70.9%).

Figure 2.

Support available to respondents

.

Support available to respondents

There was an increasing trend in the prevalence of abuse with age. While 15.8% of respondents aged 65–74 years had suffered a form of abuse, 37.5% of respondents aged 85 years and above were abused. The association between belonging to an older age group and abuse was statistically significant (OR = 3.21, CI: 1.28–8.02, P = 0.001). Also, a higher proportion of males (23.8%) than females (19.4%) reported abuse although without statistical significance (OR = 0.77, CI: 0.42–1.40, P = 0.393) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic distribution and abuse of respondents

|

Characteristic

|

Category

|

No (%)

|

Yes (%)

|

χ2

|

P

value

|

OR

|

CI

LB-UB

|

| Age |

65 – 74 years |

155 (82.4) |

29 (15.8) |

13.384 |

0.001 |

1.00 |

|

| 75 – 84 years |

44 (65.7) |

23 (34.3) |

|

|

2.79 |

1.47–5.31 |

| ≥ 85 years |

15 (62.5) |

9 (37.5) |

|

|

3.21 |

1.28–8.02 |

| Gender |

Male |

131 (76.4) |

41 (23.8) |

0.729 |

0.393 |

1.00 |

|

| Female |

83 (80.6) |

20 (19.4) |

|

|

0.77 |

0.42–1.40 |

| Income |

< 20 000 Naira |

149 (74.5) |

51 (25.5) |

4.678 |

0.031 |

1.00 |

|

| ≥ 20 000 Naira |

65 (86.7) |

10 (13.3) |

|

|

0.45 |

0.21–0.94 |

| Expenditure |

< 20 000 Naira |

154 (73.3) |

56 (26.7) |

10.353 |

0.001 |

1.00 |

|

| ≥ 20 000 Naira |

60 (92.3) |

5 (7.7) |

|

|

0.23 |

0.09–0.60 |

| Tenure of house |

Owned |

77 (72.6) |

29 (27.4) |

2.678 |

0.102 |

1.00 |

|

| Not owned |

137 (81.1) |

32 (18.9) |

|

|

0.62 |

0.35–1.10 |

| Educational level |

No formal education |

81 (70.4) |

34 (29.6) |

11.130 |

0.004 |

1.00 |

|

| Primary education |

108 (80.0) |

27 (20.0) |

|

|

0.60 |

0.33–1.07 |

| Post-primary education |

25 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

< 0.01 |

< 0.01– < 0.01 |

| Occupation |

Trading |

59 (80.8) |

14 (19.2) |

7.085 |

0.069 |

1.00 |

|

| Farming |

115 (73.2) |

42 (26.8) |

|

|

1.54 |

0.78 – 3.04 |

| Retired |

25 (83.3) |

5 (16.7) |

|

|

0.84 |

0.27 – 2.59 |

| Others |

15 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

< 0.01 |

< 0.01 – < 0.01 |

| Marital status |

Married |

154 (77.0) |

46 (23.0) |

0.284 |

0.594 |

1.00 |

|

| Unmarried |

60 (80.0) |

15 (20.0) |

|

|

0.84 |

0.43 – 1.61 |

OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, LB: Lower border; UB: Upper border.

Furthermore, 25.5% of respondents who earned less than the minimum wage were abused while 13.3% of those who earned above that were abused (OR = 0.45, CI: 0.21–0.94, P = 0.031). More (29.6%) of respondents with no formal education were abused compared with 20% and 0% of respondents with primary and post-primary education respectively. This association between level of education and abuse was also statistically significant (OR = 0.60, CI: 0.33 – 1.07, OR ≤ 0.01, CI: < 0.01 – < 0.01, P = 0.004).

Although 27.4% of those who owned their house were abused compared to 18.9% of respondents who did not own their house, this difference was not statistically significant (OR = 0.62, CI: 0.35–1.10, P = 0.102). There was also no statistically significant association between occupation, marital status, and abuse (P > 0.05).

Discussion

This study assessed the pattern and correlates of elder abuse in a local government area of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Financial abuse was the most prevalent form of abuse (13.8%) which is in contrast to the findings in studies carried out in other parts of the world. Nemati-Vakilabad et al10 in Iran, as well as Ben Natan and Ariela8 in Israel, reported neglect as the most prevalent form of abuse in their research. In addition, neglect was the most common form of abuse in the UK National Prevalence Study of Elder Mistreatment.6 The Nigeria poverty headcount ratio at $2.15 a day was 31% which ranked much higher than that of Israel and the United Kingdom at 0.5% and 0.2% respectively.21 Nigeria is one of the lower middle-income countries with about a third of her population living below the poverty line and the elderly are equally not spared which could explain the pattern of abuse seen among them.

Moreover, the finding on the commonest form of abuse in our study is also in contrast with that from similar studies done in Nigeria in which neglect was identified as the commonest form of abuse.11,12 Another study in Nigeria identified emotional abuse as the most prevalent form of elder abuse.13 This disparity may be due to the increasing sensitization to the rights of older persons which makes them identify more breaches in their finances. The differences in identified patterns of abuse among the different populations may also be the results of using different research tools in assessing the prevalence of elder abuse. Furthermore, physical and verbal forms of abuse were the least common with a prevalence of 1.8% each among respondents. This is not far-fetched because 80.4% of respondents had adequate physical support compared to 70.9% who considered their financial support adequate. This may also be a pointer to why financial abuse was more reported in this study.

There was an increasing trend in the prevalence of abuse with age in this study. This is consistent with the study by Biggs et al. where abuse was found to have worsened with age as the prevalence of financial abuse among those aged 66–74, 75–84, and ≥ 85 was 0.4%, 0.9%, and 1% respectively.6 Abuse also seems to worsen with poor health.6 As the elderly person grows older, his body organs and system undergo changes that may cause deterioration in the general health and he or she gets more socially isolated, and becomes more reliant on people for care making them exposed and more vulnerable to abuse. A higher proportion of males (23.8%) than females (19.4%) reported abuse, though there was no significant association between abuse and gender. In contrast, women were found to be affected more in the study by Akpan and Umobong.12

Also, the prevalence of abuse tends to be higher among those with low economic status compared to those with good financial standing. Abuse was also found to have worsened with illiteracy. More (29.6%) of respondents with no formal education were abused compared with 20% of respondents with primary and 0% of respondents with post-primary education respectively. This revealed the impact of socioeconomic inequality on abuse and maltreatment among the elderly population. The lower prevalence of abuse among the more educated elderly might be because those who are more educated were likely to be gainfully employed and financially stable than the less educated without requiring much help from others.22 Furthermore, the less educated elderly were less likely to be aware of their rights and lack of awareness of one’s rights may make abuse thrive more.23

Among the older population studied, financial abuse was the most prevalent form of elder abuse. Lower level of financial compared to physical support was also reported by respondents while associations were found between low educational level, low income, and abuse. Although efforts were made to verify the claims of respondents, the conclusion drawn from this study depends entirely on respondents’ responses which may be subjective and can be affected by recall bias. Additionally, the use of a cross-sectional study design limits the ability to demonstrate causation between abuse and the independent variables. Further research could consider the use of longitudinal design for investigating the cause-and-effect linkages between abuse and these factors.

Study Highlights

What is current knowledge?

What is new here?

-

The lower the houseoold income, the higher the risk of elder abuse.

-

In addition, there is a significantly higher prevalence of elder abuse among people with low education levels.

Conclusion

Elder abuse is a prevailing but silent menace among community-dwelling older persons. Since abuse is associated with low education and income, it is recommended that education should be made compulsory and affordable to all. This will ensure that as people age, they are better prepared financially, and are aware of their rights. Health workers and older persons should also be sensitized about the forms of abuse and encouraged to report them. Government can incorporate care of the elderly into health care programs. Financial support and attention should also be given to the elderly as these measures will go a long way to reduce their risk of abuse in society.

Competing Interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval (Protocol number: ERC/2014/04/15/19A) for the study was obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of the Federal Teaching Hospital, Ido-Ekiti.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Abuse of Older People [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2024. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/abuse-of-older-people. Accessed February 4, 2024.

- CDC. Fast Fact: Preventing Elder Abuse. Atlanta: Division of Violence Prevention; 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/fastfact.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Felderabuse%2Fdefinitions.html. Accessed February 4, 2024.

- Burnes D, Pillemer K, Caccamise PL, Mason A, Henderson CR Jr, Berman J. Prevalence of and risk factors for elder abuse and neglect in the community: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(9):1906-12. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13601 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017; 5(2):e147-e56. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(17)30006-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yon Y, Ramiro-Gonzalez M, Mikton CR, Huber M, Sethi D. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health 2019; 29(1):58-67. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky093 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Biggs S, Manthorpe J, Tinker A, Doyle M, Erens B. Mistreatment of older people in the United Kingdom: findings from the first National Prevalence Study. J Elder Abuse Negl 2009; 21(1):1-14. doi: 10.1080/08946560802571870 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sooryanarayana R, Choo WY, Hairi NN. A review on the prevalence and measurement of elder abuse in the community. Trauma Violence Abuse 2013; 14(4):316-25. doi: 10.1177/1524838013495963 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ben Natan M, Ariela L. Study of factors that affect abuse of older people in nursing homes. Nurs Manag (Harrow) 2010; 17(8):20-4. doi: 10.7748/nm2010.12.17.8.20.c8143 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Johnson MJ, Fertel H. Elder abuse. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Nemati-Vakilabad R, Khalili Z, Ghanbari-Afra L, Mirzaei A. The prevalence of elder abuse and risk factors: a cross-sectional study of community older adults. BMC Geriatr 2023; 23(1):616. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-04307-0 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ola TM, Olalekan A. Socio-demographic correlates of pattern of elderly abuse in Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria. Int J Humanit Soc Sci 2012; 2(20):299-306. [ Google Scholar]

- Akpan ID, Umobong ME. An assessment of the prevalence of elder abuse and neglect in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. Developing Country Studies 2013; 3(5):8-14. [ Google Scholar]

- Ekot MO. Selected demographic variables and elder abuse in Akwa Ibom state, Nigeria. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 2016; 6(2):1-15. [ Google Scholar]

- Cadmus EO, Owoaje ET, Akinyemi OO. Older persons’ views and experience of elder abuse in South Western Nigeria: a community-based qualitative survey. J Aging Health 2015; 27(4):711-29. doi: 10.1177/0898264314559893 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yussuf AJ, Baiyewu O. Elder abuse and neglect in Zaria northern Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 2014; 21(2):171-6. [ Google Scholar]

- Olasupo MG, Odunjo-Saka KA. Elder abuse in southwest Nigeria: do age group and religious affiliation play any impact?. Gender and Behaviour 2021; 19(2):18141-6. doi: 10.10520/ejc-genbeh_v19_n2_a44 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Agunbiade OM. Explanations around physical abuse, neglect and preventive strategies among older Yoruba people (60+) in urban Ibadan Southwest Nigeria: a qualitative study. Heliyon 2019; 5(11):e02888. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02888 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- National Population Commission. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. 2019. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR264/SR264.pdf.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health and Ageing. Available from: http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2014.

- Schofield MJ, Mishra GD. Validity of self-report screening scale for elder abuse: Women’s Health Australia Study. Gerontologist 2003; 43(1):110-20. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.110 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Poverty Headcount Ratio at $2.15 a Day (2017 PPP) (% of Population) - Israel, United Kingdom, Nigeria. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.DDAY?locations=IL-GB-NG&name_desc=true. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- Cairó I, Cajner T. Human capital and unemployment dynamics: why more educated workers enjoy greater employment stability. Econ J 2018; 128(609):652-82. doi: 10.1111/ecoj.12441 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Raghupathi V, Raghupathi W. The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995-2015. Arch Public Health 2020; 78:20. doi: 10.1186/s13690-020-00402-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]