J Res Clin Med. 12:17.

doi: 10.34172/jrcm.34509

Reviews

The protective effects of Helicobacter pylori: A comprehensive review

Ali Sadighi Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Zahra Aghamohammadpour Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, 1

Fatemah Sadeghpour Heravi Investigation, Resources, Writing – review & editing, 2

Mohammad Hossein Somi Visualization, 1

Kourosh Masnadi Shirazi Nezhad Visualization, 1

Samaneh Hosseini Validation, 3

Katayoun Bahman Soufiani Validation, 4

Hamed Ebrahimzadeh Leylabadlo Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, 1, *

Author information:

1Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

2Macquarie Medical School, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia

3Neurosciences Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

4Department of Laboratory Sciences and Microbiology, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Tabriz Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

Previous reports have estimated that approximately half of the world’s population is infected with Helicobacter pylori, the most prevalent infectious agent responsible for gastrointestinal illnesses. Due to the life-threatening effects of H. pylori infections, numerous studies have focused on developing medical therapies for H. pylori infections, while the commensal relationship and positive impacts of this bacterium on overall human health have been largely overlooked. The inhibitory efficacy of H. pylori on the progression of several chronic inflammatory disorders and gastrointestinal diseases has recently raised concerns about whether this bacterium should be eradicated in affected individuals or maintained in an appropriate balance depending on the patient’s condition. This review investigates the beneficial effects of H. pylori in preventing various diseases and discusses the potential association of conditions such as inflammatory disorders with the absence of H. pylori.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Gastrointestinal diseases, Eradication, Protective effect, Regulatory T cells, Dendritic cells

Copyright and License Information

© 2024 The Authors.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Spiral-shaped gram-negative bacteria, known as Helicobacter pylori, are frequently found in the human stomach. Most individuals infected with H. pylori exhibit no symptoms or serious complications.1 However, H. pylori can contribute to various gastrointestinal problems. In most cases, initial childhood infections are asymptomatic, although children may occasionally experience dizziness, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort. This asymptomatic phase underscores the importance of specific antibacterial combination therapy to prevent individuals with persistent severe gastric inflammation, commonly referred to as gastritis, from experiencing symptoms throughout their lives. While the majority of infected individuals remain asymptomatic, approximately 10% may develop peptic ulcers,2,3 and a small percentage (around 1% to 2%) may eventually develop gastric neoplasms due to the gradual progression of preneoplastic changes characterized by atrophic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia.4,5 However, it should be clarified why some patients with H. pylori experience these symptoms.1 This bacterium can remain undetected in the human body for years. Its incidence varies depending on geographical location, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, with developing countries of low socioeconomic status having higher rates of infection.6 Bacterial colonization in saliva and tooth plaque can also facilitate transmission through oral-oral contact.7,8 Despite H. pylori infection being an established cause of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer, other factors also involved in the development of H. pylori infections into gastric disorders.9 Therefore, investigating the genetic and environmental factors is crucial for understanding the causes of diseases and preventive measures.

To date, the association between various stomach morphologies with quantitative traits and H. pylori infection is still unclear. On the other hand, the role of known factors on bacterial virulence such as vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), urease, cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), and blood group antigen binding adhesion 2 (BabA2), as well as environmental factors, financial status, diet, and exposure to toxic chemicals should not be underestimated.10,11

Since the 2015 Kyoto H. pylori Conference’s agreement, there have been substantial

modifications to the strategy regarding the H. pylori management. In the case of H. pylori infection, eradication is recommended now unless there are justifiable reasons not to eradicate it. These reasons may include co-existing medical conditions, higher re-infection rates in the area, or other essential health considerations.12 This strategy raises concerns due to H. pylori antibiotic resistance during the past decades. This issue is exacerbated by a lack of effective therapeutic options and extensive public consumption of drugs.13,14 Additionally, H. pylori species exhibit an unusually high capacity for adaptation, leading to the rapid development of primary antibiotic resistance. Although treatment success rates vary by location and region, the efficacy of eradication medications has progressively declined over time.13,15,16

Since 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) has classified H. pylori as one of the top 20 drug-resistant pathogens posing a significant threat to human health.17 Addressing this global issue necessitates the implementation of various measures by clinicians, including the use of new treatment methods, optimization of empirical therapies, and personalized treatments.18

H. pylori instigates a potent immune response, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-17, IL-6, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), are produced by immune-responsive cells such as T-helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17, and Treg cells.19,20 While activation cytokines are generally considered detrimental, H. pylori-regulated cytokine production may play a beneficial role in certain conditions. Many studies have found that H. pylori regulates the expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-1β, which play crucial roles in preventing several disorders.21

While studying H. pylori infections and treatment approaches is critical, researchers must also consider the bacterium’s beneficial effects on host physiology. Eradication procedures may have more significant consequences than its presence in the human gastrointestinal system.8 Common diseases associated with the “protective” significance of H. pylori infection include allergies and asthma,22 gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD),21 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),23 autoimmune diseases,24 allergic disorders,25 eosinophilic esophagitis 26, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).27

The protective effects of Helicobacter pylori in various diseases

Allergies and asthma

Previous research has shown a link between the incidence of allergies (e.g., asthma), environmental factors, and microbes.28 The immune system can mature and defend against immunologically-mediated diseases when exposed to the environment and bacteria.29 For example, studies have demonstrated that early childhood exposure to various microorganisms can help to prevent allergies later.30

The connection between H. pylori and asthma has recently gained significant attention. By modifying the ratio of Th1/Th2, Th17/regulatory T cells (Tregs), and other variables, H. pylori can prevent allergic asthma. Additionally, H. pylori can target dendritic cells to enhance immunological tolerance and the ability to prevent allergic asthma.31-35 The H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) is crucial in this context.

In both in vitro and in vivo studies, HP-NAP has been shown to have protective effects in asthma, stimulating type 1 T helper (Th1) responses, and reducing Th2 reactivity in allergy-related asthma.36-38 However, the mechanisms of asthma and H. pylori are not solely explained by the Th1/Th2 ratio.39,40 In addition, Tregs and Th17 cells are associated with the pathogenesis of asthma. Moreover, the interplay between Th17 and Th2 inflammatory processes has been observed in asthma.41 Subsequently, Th17/Tregs and Th1/Th2 interaction results in a complex and extensive network with their respective cytokines.41,42 In turn, Th17 cells produce IL-17, which can promote inflammatory responses by stimulating neutrophil maturation, immune cell proliferation, and chemotaxis.43 On the other hand, Tregs release IL-10 and other inhibitory cytokines that play crucial roles in regulating immune responses. For instance, Treg cells promote immune tolerance and suppress immune responses through the activation of forkhead transcription factor p3,43,44 a protective mechanism associated with H. pylori in preventing asthma.45,46

Previous research indicates that H. pylori can upregulate the Th1, Tregs, and Th17 genes in both experimental and clinical settings, potentially in terms of asthma prevention.24 Dendritic cells (DCs) have been proposed as a target of H. pylori to enhance immunological resistance and protective mechanisms against allergic asthma. This mechanism mainly relies on the suppression of Tregs.24,47 Additionally, Shiu et al. revealed that H. pylori can enhance cellular responses that quench inflammation, such as IRAK-M (IL-1 receptor-associated kinase M).48 IRAK-M expression, activated by toll-like receptors (TLRs) in DCs, inhibits DC function, including the upregulation of cytokines and co-stimulatory molecules, without affecting their response to Th17 and Tregs.

Calling attention, H. pylori has been shown to trigger a cascade of inflammatory responses and activation of various inflammatory factors in both mouse and human immune cells.49,50 For instance, H. pylori-induced IL-1β can stimulate Th17 and Th1 activation.51 In mouse models, several receptors, including nod-like receptor family members (NLRP3), caspase-1, and TLR2, regulate the release of IL-1β induced by H. pylori. These receptors play a role in inhibiting hypersensitive reactions such as asthma.49,51,52 Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 1 (NOD1) is an intracellular pattern-recognition receptor (PRR) that recognizes bacterial components and initiates inflammation pathways. Variations in the NOD1 gene have been genetically linked to asthma.53 These gene variations are associated with IBDs and asthma. NOD1 has been shown to induce minimal production of TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-1β from human peripheral blood while synergistically enhancing TLRs-induced responses. This synergistic effect involves the release of multiple cytokines and multiple ligands.54,55

Inflammatory bowel disease

IBD, which encompasses chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal (GI) system such as ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), has been the subject of several observational studies to investigate the possible link with H. pylori. Recently, the presence of H. pylori in the intestinal mucosa of IBD patients, colorectal neoplasms, and normal colonic mucosa has been reported.56-58 However, a meta-analysis study has shown that individuals with IBD have a lower incidence of H. pylori compared to non-IBD patients.59,60 These conflicting findings may suggest that the prevalence of H. pylori-related disease in individuals with IBD could be influenced by some factors like ethnicity.

Further studies declared that individuals with IBD who received antibiotics had a lower H. pylori infection rate compared to those without antibiotics treatment.60,61 A study included 153 patients with severe UC showed significantly lower rates of H. pylori infection compared to the control group. Another study found that patients with small intestine and ileocolonic CD had remarkably lower rates of H. pylori infection than those in the control group.62 However, in a different study, only 13% of IBD individuals were found to have H. pylori, while the frequency ranged from 39% to 67% in the control group. This finding was corroborated by Polish research involving ninety-four children with IBD, which indicated a lower prevalence of H. pylori in individuals with IBD.63

Similarly, a recent meta-analysis of thirty research projects also suggested potential protective roles of H. pylori, with only 27% of IBD individuals presenting signs of H. pylori-related disease.64 However, the researchers emphasized that the variability in study design could affect the certainty of their conclusions. Therefore, further research is needed to fully understand the protective effects of H. pylori in both affected and healthy individuals.

Animal studies have also indicated that chronic infection with H. pylori may change the pattern of microbiota in the large intestine, potentially influencing the development of IBD.65 Research on animal colitis models has also suggested that H. pylori infection could modulate immune responses, leading to the host being less susceptible to other chronic inflammatory disorders like IBD.64-66

In this line, Papamichael et al. suggested that H. pylori infection may protect against IBD through mechanisms such as elevating cytokine levels, stimulating T cells and dendritic cells, and suppressing the Th1/Th17 process.23,67,68 A similar study has also demonstrated the protective effect of H. pylori on colitis due to the bacteria’s chromosomal DNA, containing a high frequency of immune-regulatory sequences, which is sufficient to intercept sodium dextran sulfate-induced colitis. In the animal model, rats were treated with an oral administration of H. pylori DNA before being subjected to chronic and acute colitis; in both groups, the DNA-based treatment reduced virulence and other factors related to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis.66 The protective effect of H. pylori DNA was attributed to its ability to inhibit cytokine release by dendritic cells. However, it is not yet determined whether or not H. pylori DNA can protect against IBD development in human or mouse models.

Gastro- oesophageal reflux disease

GERD, a common disorder, irritating the squamous epithelium of the esophagus, involves the passage of stomach contents into the esophagus.69 On the contrary, GERD has been linked to H. pylori infection and Barrett’s esophagus (BO), especially the cagA+ strain.8,70 Previously, no differences in the prevalence of H. pylori were observed between patients with GERD and the control group. However, the coexistence of cagE and cagA genes of H. pylori was more common in the control group.71 Similarly, Bor et al found that the presence of H. pylori had no impact on the frequency of GERD or the associated symptom profile.72 In this respect, a methodological analysis has also indicated that the incidence of H. pylori is significantly lower in individuals with GERD. Despite controversial findings, it has been demonstrated that GERD incidence tends to be lower in individuals infected with H. pylori, potentially suggesting a protective role of H. pylori against GERD development.73 Moreover, it has been posited that the occurrence of GERD escalates after the successful elimination of Helicobacter pylori.21

Of note, corpus-predominant gastritis caused by H. pylori, especially the CagA-positive strain, can reduce gastric acid secretion and prevent damage to the esophageal epithelium.74,75 Additionally, H. pylori can influence the production of leptin and ghrelin in the stomach, and gastric acid release.59,60 Furthermore, H. pylori DNA has been shown to systemically downregulate pro-inflammatory responses, including type 1 interferon and IL-12 cytokines, which can minimize the occurrence of erosive esophagitis (EO).64,76,77

Similarly, another study suggests that the elimination of H. pylori may result in the development of GERD. The risk of developing new GERD is approximately twofold in individuals experienced H. pylori eradication. However, eradicating H. pylori may not affect the therapeutic or recurrence rates of pre-existing GERD. Noteworthy, given the wide array of variables, including H. pylori virulence factors, host physiology, genetics, lifestyle, and geographical factors, further research is needed to evaluate the impact of H. pylori on the onset of GERD.70

Eosinophilic esophagitis

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a type of immune-mediated esophageal dysfunction, characterized by esophageal dysfunction symptoms, frequent eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal mucosa, and food impaction,78 in which, recent studies have suggested a beneficial impact of H. pylori on EoE.26 In this regard, Cheung et al. showed lower rates of H. pylori-related infection in Australian children with EoE compared to the control group.79 Ronkainen et al. also found that Swedish adults with EoE were at a lower risk of severe complications related to H. pylori compared to the control group.80-82

There are two opinions regarding the protective impact of H. pylori in EoE patients: (1) EoE is typically characterized by a TH2-polarized allergic reaction, while the bacteria elicit a Th1 immune response, and (2) Increasing concerns suggest that the reduction in H. pylori incidence over the past few decades has been associated with an increase in EoE prevalence.83-86

Notably, H. pylori infections have been found to result in a complicated, Th1/Th17-dominated immune response rather than a purely Th1-polarized response, promoting the differentiation of anti-inflammatory Th2 cells.87 Additionally, EoE patients with delayed onset and severe allergic inflammation have shown IL-17-positive cell expansion influenced by both Th1 and Th17 cytokine profiles.88 Recent research in adults and children with EoE has also indicated that Th17 plays a crucial role in disease progression.88

Several studies have previously suggested common pathogenic factors between EoE and H. pylori. Galectin-3 (Gal-3) has a critical function in H. pylori pathogenicity in the stomach lining, immune responses, and chronic gastric consequences.89 In this regard, Gal-3 could be a crucial host component for maintaining subclinical H. pylori infection and colonization levels.89,90 In vitro studies have also demonstrated that Gal-3 is an essential factor for the activation of human basophils in IgE-dependent conditions rather than EoE.89 Mast cells, known immune cells involved in both H. pylori infection virulence and EoE virulence,91,92 are thought to play a significant role in EoE development. They can stimulate the inflammatory pathways and fibrosis in EoE through the secretion of TGF-β, which stimulates proliferation and collagen release.93,94 TGF-β is also believed to be a facilitating factor in H. pylori pathogenesis. Moreover, H. pylori-derived VacA cytotoxin has chemotactic effects on mast cells derived from bone marrow (BMDMCs), leading to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, which has high expression in the esophageal epithelial cells of EoE.26,95

During infection with H. pylori, the gastric epithelial cells actively engaged in signaling pathways mediated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase to intensify the production of IL-33. This intricate process was contingent upon cagA, a crucial factor, leading to heightened inflammation and an augmented bacterial load within the protective lining of the stomach. In hence, H. pylori-associated mast cell-associated TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-33 may be involved in the pathophysiology of EoE, and further research is needed to explore this field.26

According to the literature, another granulocyte associated with EoE is basophils,96,97 however, the exact role of H. pylori-derived peptides as strong basophil chemo-attractants in the severity of EoE remains to be determined.26 Regarding H. pylori infection, a few studies have shown that Th1 and Th17 cells exhibit dual effects.

The anti-inflammatory effects following H. pylori infection can be regulated by Treg and Th2 cells. Noteworthy, reduced esophageal expression of hBD1 and hBD3 has been also identified during EoE, suggesting that the esophageal mucosa could be more vulnerable to the EoE incident.98,99 Despite H. pylori can evade defensin attack, human defensins (small proteins produced by circulating white blood cells and tissue cells) may play a crucial role in H. pylori-associated neurodegenerative diseases, as the bacterium induces defensin release in response to persistent inflammatory tissue injury.100,101

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

ESCC ranks as the 8th fatal malignancies malignancy, accounting for 90% of the 456,000 esophageal cancers diagnosed each year.102,103 Previous studies have suggested that H. pylori infection may act as a protective factor for GERD and the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EA).74,104-106 Ye et al for the first time established the association between ESCC and CagA-positive H. pylori infections in the Swedish population via serological assessment.107 A similar correlation was recently observed in Japan.108 The potential mechanism of this effect may be derived from stomach atrophy, low intragastric acidity, and increased intragastric NH3 secretion following H. pylori infection.

Besides, Barrett’s esophagus plays a substantial role in the development of EA.109,110 A Barrett’s ulcer can occur due to recurrent gastroesophageal reflux,110 causing chronic inflammation and mucosal damage, leading to the replacement of squamous epithelium with intestinal-type epithelium in an acidic microenvironment.111 Infection with H. pylori, especially cagA + strains, accelerates hypochlorhydria, and a lower pH environment results from multifocal stomach atrophy.111 Therefore, H. pylori’s “protective” role could be attributed to reduced gastric reflux potency in individuals with corpus-predominant gastritis or decreased esophageal movements.112,113

However, another study demonstrated that H. pylori has the potential to cause cell death in Barrett ‘s-derived esophageal adenocarcinoma cells through the Fas-caspase cascade.114 The effect of H. pylori infection on acid secretion can vary depending on the gastritis pattern it induces.115 H. pylori infection should not be considered a single entity regarding its role in acid secretion and its impact on esophageal reflux disease and its consequences.116 Patients with gastric ulcers typically have atrophic gastritis and normal or reduced acid secretion, while patients with duodenal ulcers often have H. pylori antral predominance, non-atrophic gastritis, and increased acid secretion.117-119

The literature suggests that patients with duodenal ulcers infected with H. pylori have a higher risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma, whereas no such relationship has been found with gastric ulcers. This observation supports the idea that H. pylori infection is not the sole factor responsible for inducing reflux disease. Therefore, patients with H. pylori infection who experience excessive acid secretion due to antral-predominant, non-atrophic gastritis may be at a higher risk of developing EA.120

The disparity in findings can be explained by the pattern of gastritis induced by H. pylori infection, which determines the potential impact on reflux disease.120,121 Infection with H. pylori is associated with a higher likelihood of developing atrophic gastritis and reduced acid secretion, which may protect against reflux disease.120,121 Conversely, the infection is typically associated with antral-predominant and non-atrophic gastritis in the West countries.122

Autoimmune diseases

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurological disease that affects the nervous system i.e., the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve, and significantly influences the quality of life.123 In MS, similar to the pathogenicity observed in IBD, the Th17 subset of helper T-cells plays a central role in chronic (neuro-) inflammation.124 It is now widely understood that Th17 cells, previously thought to be Th1 cells, are the primary encephalitogenic population in autoimmune neuroinflammation, particularly in the experimental model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) known as a conventional mouse model of MS.125

Of note, recent literature has shown that autoreactive helper T-cells expressing IFN-γ and IL-17A but lacking GM-CSF were unable to induce neuroinflammation. However, the secretion of GM-CSF by Ifng−/−Il17a−/− helper T-cells was sufficient to cause EAE. There is compelling evidence indicating that Th17-derived GM-CSF plays a dominant role in autoimmune CNS inflammation. Compelling data suggest a protective role for H. pylori in the development of MS.126

Conversely, a contradictory association between H. pylori infection and MS development was found among the Japanese people.127 Some pieces of literature have suggested a higher incidence of MS in adults with a history of asthma since childhood.128 In a study involving 105 MS patients and 85 non-MS healthy controls, individuals with MS had significantly lower seropositivity to Helicobacter pylori than those without MS.127 These findings need further confirmation in larger cohorts and should be empirically tested in the MS EAE model. In EAE, the tail and hind limbs become sensitive to H. pylori-induced Treg-mediated immunoregulation due to CNS inflammation and progressive supranuclear palsy caused by myelin-specific auto aggressive T cells.126

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is a syndrome characterized by dysfunction in the skin and various internal organs and is typically categorized as a group of autoimmune connective tissue diseases.129,130 A study demonstrated that H. pylori urease may induce the production of anti-ssDNA in rats. It is also believed that H. pylori has a preventive effect on the progression of SLE.131

Another research study examined the prevalence of H. pylori seropositivity in 466 lupus patients compared to matched controls and found that fewer SLE patients were seropositive for H. pylori, suggesting that H. pylori did not contribute to the development of SLE. However, it had a protective effect against the progression of the disease.132 Subgroup analysis revealed that African-American women seropositive for H. pylori were more likely to develop lupus in their later years compared to H. pylori-negative SLE patients.133 However, the exact mechanism underlying this association remains unclear.

Shapira et al. also reported higher levels of anti-H. pylori antibodies in patients with giant cell arteritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and primary biliary cirrhosis.134 A study conducted in 2002 by Kalabay et al found that 82% of individuals with connective tissue diseases were infected with H. pylori.135 However, another study indicated that H. pylori infection did not play a role in SLE development but rather involved in preventing the disease from progressing.132

Rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common systemic inflammatory joint disorder.136 The initial evidence of a link between RA and H. pylori infection was presented by Yamanishi et al, who demonstrated that H. pylori urease could stimulate B cells to produce IgM rheumatoid factor.131 However, other studies found no association between the presence of H. pylori and RA. The rate of H. pylori infection was higher in the control group than in RA patients.132,137

Additionally, a growing body of evidence has reported a significant correlation between the eradication of H. pylori and the development of RA.138-140 Recent research has shown that RA patients who use non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have a higher incidence of peptic ulcers. According to Janssen et al, H. pylori infections are less common in RA patients who use NSAIDs.137,141

Systemic sclerosis

Systemic sclerosis (SS) is an autoimmune disease that affects the abnormal development of connective tissues 142. In one study involving twelve European scleroderma patients, 42% (5 individuals) were found to have H. pylori infection.143 In a larger cohort study of 124 Japanese patients with systemic sclerosis, the seroprevalence of H. pylori was 55.6%, significantly higher than in healthy controls.90 Another study involving a different group of patients (n=64) in Japan suggested that H. pylori infection may have protective effects against the progression of reflux esophagitis in individuals with scleroderma144 (Figure 1).

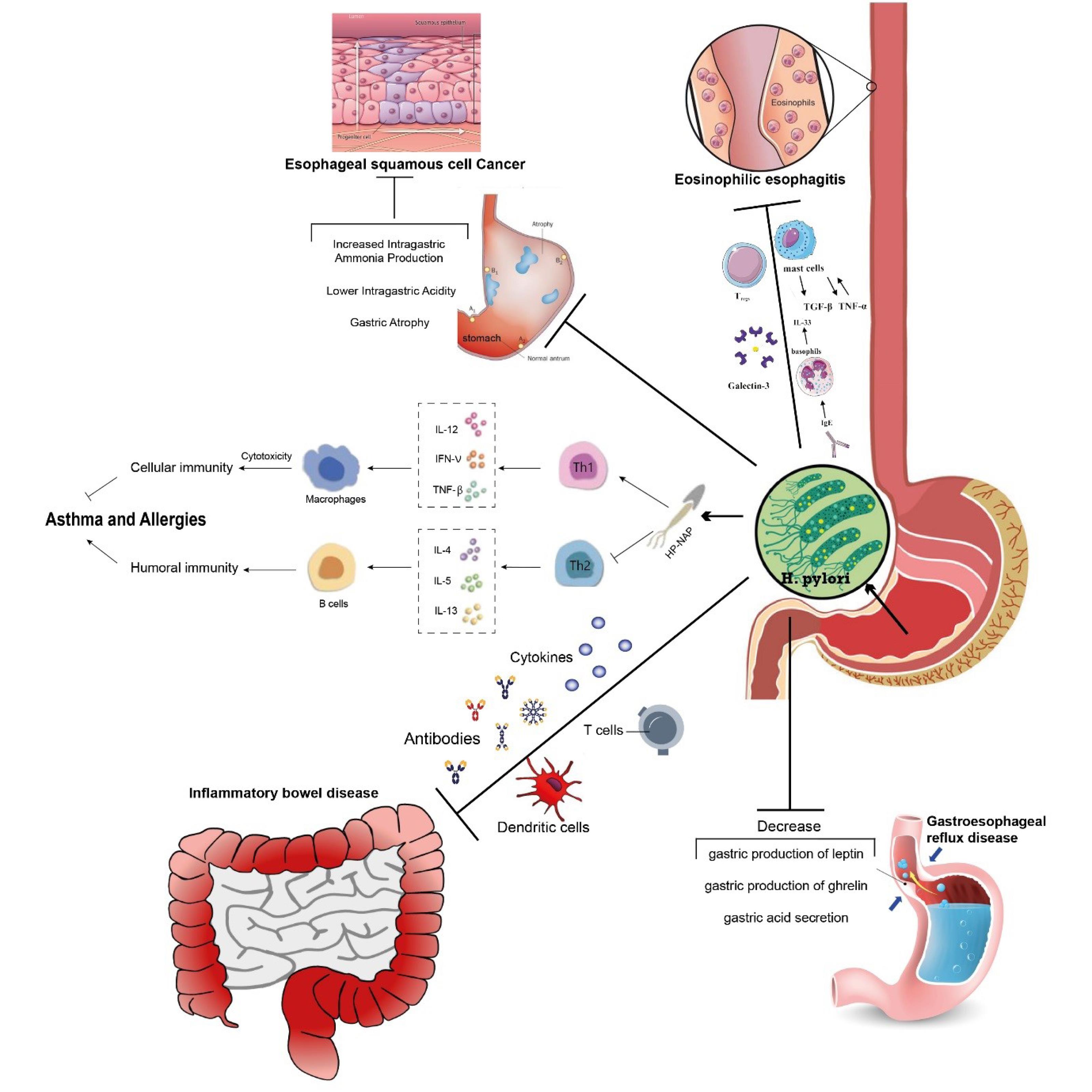

Figure 1.

Probable protective mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori in various diseases. Abbreviations: Ig (immunoglobulin), IL (interleukin), TGF (transforming growth factor), TNF (tumor necrosis factor), Tregs (regulatory T cells), HP-NAP (H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein), Th1/Th2 (Helper T cells 1/2)

.

Probable protective mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori in various diseases. Abbreviations: Ig (immunoglobulin), IL (interleukin), TGF (transforming growth factor), TNF (tumor necrosis factor), Tregs (regulatory T cells), HP-NAP (H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein), Th1/Th2 (Helper T cells 1/2)

Other diseases

Celiac disease

CD is an immune-related gluten allergy that affects the small intestine, resulting in both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal symptoms.145 Research has shown a strong inverse correlation between the presence of H. pylori and the development of CD in patients undergoing gastrointestinal endoscopy for various symptoms. H. pylori recruits T-regulatory lymphocytes, which have protective effects against allergen-induced asthma and systemic implications.47,146,147 T-regulatory lymphocytes are also involved in the etiology of CD. In patients with CD, there is a decrease in the number of receptors for cellular responses facilitated by T-regulatory cells in the bowel wall, and these receptors are impaired or absent.48 Therefore, lacking functional gastric T-regulatory cells and H. pylori may not be able to reduce the number of immune response receptors to gluten. Instead, H. pylori may influence the absorption of gluten by altering gastric pH or using proteases, thereby reducing its immunogenicity.1,148,149

Diarrheal disease

Diarrheal diseases are the most prevalent infectious causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide.150 H. pylori may play protective roles against exogenous pathogens by activating specific local and systemic immunoglobulins or by secreting antibacterial peptides.151,152 While it has not been extensively studied, many researchers suggest that H. pylori protects against diarrheal diseases.150,151,153 The protective mechanisms may involve the secretion of antibacterial peptides by either the host or H. pylori, immune system stimulation as an adjuvant, competition for a niche, or the maintenance of gastric acid through hypergastrinemia throughout childhood.154 The innovation of clean water, improved quality of life, and reduced population density have led to a lower prevalence of deadly diarrheal diseases, which may be linked to reduced transmission of H. pylori and decreased selection for its maintenance.155

Tuberculosis

There is a notable inverse association between H. pylori infection and tuberculosis. Recent research conducted in tuberculosis-prone areas of West Africa has demonstrated that individuals with H. pylori infections had a lower risk of reactivating latent tuberculosis infections.156 It is suggested that H. pylori infection may enhance the host’s innate immune response and alter the risk of active tuberculosis in both humans and non-human primates by inducing bystander suppression characterized by ongoing inflammation and T-cell signaling.156,157

Metabolism and obesity

The mammalian stomach plays a role in secreting approximately five to ten percent of the body’s leptin and sixty to eighty percent of ghrelin.158 These hormones are involved in the regulation of body weight. Multiple studies have demonstrated that individuals with H. pylori infection tend to have lower levels of ghrelin compared to those without the infection, and the removal of H. pylori has been associated with an increase in ghrelin production.159-161 The presence or absence of H. pylori infection can have significant long-term metabolic effects due to ghrelin’s biological functions throughout the body.162 However, the impact on leptin function remains unclear, with seemingly conflicting results that may be influenced by risk factors such as age, medications, and the severity of gastric inflammation.76,163

Regardless of the specific effects, the overall energy balance in the population may be influenced by changes in ghrelin and leptin production resulting from the increasing number of children growing up without H. pylori’s presence in stomach physiology.164

Conclusion

In conclusion, H. pylori infection is widespread and potentially dangerous, causing fatal outcomes. Given that several gastrointestinal problems, including non-cardia gastric adenocarcinoma, gastric lymphoma, and peptic ulcers, have been previously linked to H. pylori infection. Additionally, this infection can lead to various disorders beyond the digestive system. The text explains that H. pylori have the potential to offer protection within or outside the digestive system, effectively preventing the occurrence or progression of certain diseases or in the absence of this bacterium, Some disorders can be aggravated. The beneficial or detrimental effects of H. pylori on individuals may be influenced by various factors, including host physiology, lifestyle, H. pylori virulence, and genetic factors. The broad eradication of H. pylori in recent decades, meanwhile, is now widely acknowledged to have unanticipated and undesirable effects. Therefore, the general treatment of H. pylori infections may not always be useful and may even be harmful in cases of early-stage gastric illness unlikely to proceed to gastric cancer or other serious outcomes. It is highly recommended that the pathogenicity of H. pylori in each case should be taken into account when treating H. pylori infections, as well as the patient’s medical history and clinical situation.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the support of the Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Center [Grant number: 72159]. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Liver and Gastrointestinal Diseases Research Centre, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

References

- McColl KE. Clinical practice Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(17):1597-604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Okuda M, Lin Y, Kikuchi S. Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019; 1149:107-20. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_361 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yuan C, Adeloye D, Luk TT, Huang L, He Y, Xu Y. The global prevalence of and factors associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2022; 6(3):185-94. doi: 10.1016/s2352-4642(21)00400-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lee YC, Dore MP, Graham DY. Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Annu Rev Med 2022; 73:183-95. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042220-020814 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Öztekin M, Yılmaz B, Ağagündüz D, Capasso R. Overview of Helicobacter pylori infection: clinical features, treatment, and nutritional aspects. Diseases 2021; 9(4):66. doi: 10.3390/diseases9040066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sjomina O, Pavlova J, Niv Y, Leja M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2018; 23 Suppl 1:e12514. doi: 10.1111/hel.12514 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A, Furuta T, Gisbert JP, O’Morain C. Review - treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection 2020. Helicobacter 2020; 25 Suppl 1:e12743. doi: 10.1111/hel.12743 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47(7):868-76. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gravina AG, Zagari RM, De Musis C, Romano L, Loguercio C, Romano M. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(29):3204-21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Stein SC, Faber E, Bats SH, Murillo T, Speidel Y, Coombs N. Helicobacter pylori modulates host cell responses by CagT4SS-dependent translocation of an intermediate metabolite of LPS inner core heptose biosynthesis. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13(7):e1006514. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006514 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Abbasian MH, Abbasi B, Ansarinejad N, Motevalizadeh Ardekani A, Samizadeh E, Gohari Moghaddam K. Association of interleukin-1 gene polymorphism with risk of gastric and colorectal cancers in an Iranian population. Iran J Immunol 2018; 15(4):321-8. doi: 10.22034/iji.2018.39401 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, Graham DY, El-Omar EM, Miura S. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Gut 2015; 64(9):1353-67. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Thung I, Aramin H, Vavinskaya V, Gupta S, Park JY, Crowe SE. Review article: the global emergence of Helicobacter pylori antibiotic resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43(4):514-33. doi: 10.1111/apt.13497 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kasahun GG, Demoz GT, Desta DM. Primary resistance pattern of Helicobacter pylori to antibiotics in adult population: a systematic review. Infect Drug Resist 2020; 13:1567-73. doi: 10.2147/idr.s250200 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence consensus report. Gut 2017; 66(1):6-30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C. Worldwide H pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2010; 19(4):409-14. [ Google Scholar]

- Tacconelli E, Carrara E, Savoldi A, Harbarth S, Mendelson M, Monnet DL. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18(3):318-27. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30753-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tshibangu-Kabamba E, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter pylori infection and antibiotic resistance - from biology to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 18(9):613-29. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00449-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- White JR, Winter JA, Robinson K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: etiology and clinical outcomes. J Inflamm Res 2015; 8:137-47. doi: 10.2147/jir.s64888 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jan I, Rather RA, Mushtaq I, Malik AA, Besina S, Baba AB. Helicobacter pylori subdues cytokine signaling to alter mucosal inflammation via hypermethylation of suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 gene during gastric carcinogenesis. Front Oncol 2020; 10:604747. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.604747 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Labenz J, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: causal agent, independent or protective factor?. Gut 1997; 41(3):277-80. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.277 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zuo ZT, Ma Y, Sun Y, Bai CQ, Ling CH, Yuan FL. The protective effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on allergic asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2021; 182(1):53-64. doi: 10.1159/000508330 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wu XW, Ji HZ, Yang MF, Wu L, Wang FY. Helicobacter pylori infection and inflammatory bowel disease in Asians: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15):4750-6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4750 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Müller A. The immunomodulatory properties of Helicobacter pylori confer protection against allergic and chronic inflammatory disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2012; 2:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Akiner U, Yener HM, Gozen ED, Kuzu SB, Canakcioglu S. Helicobacter pylori in allergic and non-allergic rhinitis does play a protective or causative role?. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2020; 277(1):141-5. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05659-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Doulberis M, Kountouras J, Rogler G. Reconsidering the “protective” hypothesis of Helicobacter pylori infection in eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2020; 1481(1):59-71. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14449 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhuo X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhuo W, Zhu Y, Zhang X. Helicobacter pylori infection and oesophageal cancer risk: association studies via evidence-based meta-analyses. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008; 20(10):757-62. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.07.005 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Murrison LB, Brandt EB, Myers JB, Hershey GKK. Environmental exposures and mechanisms in allergy and asthma development. J Clin Invest 2019; 129(4):1504-15. doi: 10.1172/jci124612 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jones MG. Understanding of the molecular mechanisms of allergy. Methods Mol Biol 2019; 2020:1-15. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9591-2_1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Leaker BR, Singh D, Lindgren S, Almqvist G, Eriksson L, Young B. Effects of the toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) agonist, AZD8848, on allergen-induced responses in patients with mild asthma: a double-blind, randomised, parallel-group study. Respir Res 2019; 20(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1252-2 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McAleer JP, Kolls JK. Contributions of the intestinal microbiome in lung immunity. Eur J Immunol 2018; 48(1):39-49. doi: 10.1002/eji.201646721 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- He Y, Wen Q, Yao F, Xu D, Huang Y, Wang J. Gut-lung axis: the microbial contributions and clinical implications. Crit Rev Microbiol 2017; 43(1):81-95. doi: 10.1080/1040841x.2016.1176988 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chiu L, Bazin T, Truchetet ME, Schaeverbeke T, Delhaes L, Pradeu T. Protective microbiota: from localized to long-reaching co-immunity. Front Immunol 2017; 8:1678. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01678 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fouda EM, Kamel TB, Nabih ES, Abdelazem AA. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity protects against childhood asthma and inversely correlates to its clinical and functional severity. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2018; 46(1):76-81. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2017.03.004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167(8):821-7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hong ZW, Yang YC, Pan T, Tzeng HF, Fu HW. Differential effects of DEAE negative mode chromatography and gel-filtration chromatography on the charge status of Helicobacter pylori neutrophil-activating protein. PLoS One 2017; 12(3):e0173632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173632 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ness-Jensen E, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Lu Y. Helicobacter pylori in relation to asthma and allergy modified by abdominal obesity: the HUNT study in Norway. World Allergy Organ J 2019; 12(5):100035. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100035 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Melby KK, Carlsen KL, Håland G, Samdal HH, Carlsen KH. Helicobacter pylori in early childhood and asthma in adolescence. BMC Res Notes 2020; 13(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s13104-020-04941-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wang ZE, Zhou XN, Yang Y, Liu ZY. [Effect of Jian’erle granule on Thl7/Treg imbalance of asthma mice]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2016; 36(12):1510-4. [ Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Li XM, Zhang GR, Cheng Y, Chen X, Gu W. TNF-TNFR2 signaling inhibits Th2 and Th17 polarization and alleviates allergic airway inflammation. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2019; 178(3):281-90. doi: 10.1159/000493583 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Choy DF, Hart KM, Borthwick LA, Shikotra A, Nagarkar DR, Siddiqui S. TH2 and TH17 inflammatory pathways are reciprocally regulated in asthma. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7(301):301ra129. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab3142 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li HT, Lin YS, Ye QM, Yang XN, Zou XL, Yang HL. Airway inflammation and remodeling of cigarette smoking exposure ovalbumin-induced asthma is alleviated by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides via affecting dendritic cell-mediated Th17 polarization. Int Immunopharmacol 2020; 82:106361. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106361 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kardan M, Rafiei A, Ghaffari J, Valadan R, Morsaljahan Z, Haj-Ghorbani ST. Effect of ginger extract on expression of GATA3, T-bet and ROR-γt in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with allergic asthma. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2019; 47(4):378-85. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2018.12.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Nemattalab M, Shenagari M, Taheri M, Mahjoob M, Nazari Chamaki F, Mojtahedi A. Co-expression of interleukin-17A molecular adjuvant and prophylactic Helicobacter pylori genetic vaccine could cause sterile immunity in Treg suppressed mice. Cytokine 2020; 126:154866. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2019.154866 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jafarzadeh A, Larussa T, Nemati M, Jalapour S. T cell subsets play an important role in the determination of the clinical outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Microb Pathog 2018; 116:227-36. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.040 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lehours P, Ferrero RL. Review: Helicobacter: inflammation, immunology, and vaccines. Helicobacter 2019; 24 Suppl 1:e12644. doi: 10.1111/hel.12644 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Altobelli A, Bauer M, Velez K, Cover TL, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori VacA targets myeloid cells in the gastric lamina propria to promote peripherally induced regulatory T-cell differentiation and persistent infection. mBio 2019; 10(2):e00261-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00261-19 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shiu J, Czinn SJ, Kobayashi KS, Sun Y, Blanchard TG. IRAK-M expression limits dendritic cell activation and proinflammatory cytokine production in response to Helicobacter pylori. PLoS One 2013; 8(6):e66914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066914 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pachathundikandi SK, Müller A, Backert S. Inflammasome activation by Helicobacter pylori and its implications for persistence and immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2016; 397:117-31. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-41171-2_6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Koch KN, Hartung ML, Urban S, Kyburz A, Bahlmann AS, Lind J. Helicobacter urease-induced activation of the TLR2/NLRP3/IL-18 axis protects against asthma. J Clin Invest 2015; 125(8):3297-302. doi: 10.1172/jci79337 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pachathundikandi SK, Blaser N, Backert S. Mechanisms of inflammasome signaling, microRNA induction and resolution of inflammation by Helicobacter pylori. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2019; 421:267-302. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-15138-6_11 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Blosse A, Lehours P, Wilson KT, Gobert AP. Helicobacter: inflammation, immunology, and vaccines. Helicobacter 2018; 23(Suppl 1):e12517. doi: 10.1111/hel.12517 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ying L, Ferrero RL. Role of NOD1 and ALPK1/TIFA signalling in innate immunity against Helicobacter pylori infection. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2019; 421:159-77. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-15138-6_7 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- van Heel DA, Ghosh S, Butler M, Hunt K, Foxwell BM, Mengin-Lecreulx D. Synergistic enhancement of toll-like receptor responses by NOD1 activation. Eur J Immunol 2005; 35(8):2471-6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526296 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ng MT, Van’t Hof R, Crockett JC, Hope ME, Berry S, Thomson J. Increase in NF-kappaB binding affinity of the variant C allele of the toll-like receptor 9 -1237T/C polymorphism is associated with Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric disease. Infect Immun 2010; 78(3):1345-52. doi: 10.1128/iai.01226-09 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Keenan JI, Beaugie CR, Jasmann B, Potter HC, Collett JA, Frizelle FA. Helicobacter species in the human colon. Colorectal Dis 2010; 12(1):48-53. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01672.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bulajic M, Stimec B, Ille T, Jesenofsky R, Kecmanovic D, Pavlov M. PCR detection of Helicobacter pylori genome in colonic mucosa: normal and malignant. Prilozi 2007; 28(2):25-38. [ Google Scholar]

- Jones M, Helliwell P, Pritchard C, Tharakan J, Mathew J. Helicobacter pylori in colorectal neoplasms: is there an aetiological relationship?. World J Surg Oncol 2007; 5:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-51 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y, Jing Z, Bie M, Xu C, Hao X, Wang B. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99(37):e21832. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000021832 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pang Z, Li MF, Zhao HF, Zhou CL, Shen BW. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Chinese Han patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2009; 17:3661-5. [ Google Scholar]

- Varas Lorenzo M, Muñoz Agel F, Sánchez-Vizcaíno Mengual E. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with inflammatory bowel disease for prevention of recurrences-impact on the natural history of the disease. Eurasian J Med Oncol 2019; 3(1):59-65. doi: 10.14744/ejmo.2018.0058 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Xiang Z, Chen YP, Ye YF, Ma KF, Chen SH, Zheng L. Helicobacter pylori and Crohn’s disease: a retrospective single-center study from China. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(28):4576-81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i28.4576 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sładek M, Jedynak-Wasowicz U, Wedrychowicz A, Kowalska-Duplaga K, Pieczarkowski S, Fyderek K. [The low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease children and adolescent]. Przegl Lek 2007;64 Suppl 3:65-7. [Polish].

- Luther J, Owyang SY, Takeuchi T, Cole TS, Zhang M, Liu M. Helicobacter pylori DNA decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine production by dendritic cells and attenuates dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis. Gut 2011; 60(11):1479-86. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.220087 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Heimesaat MM, Fischer A, Plickert R, Wiedemann T, Loddenkemper C, Göbel UB. Helicobacter pylori induced gastric immunopathology is associated with distinct microbiota changes in the large intestines of long-term infected Mongolian gerbils. PLoS One 2014; 9(6):e100362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100362 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Higgins PD, Johnson LA, Luther J, Zhang M, Sauder KL, Blanco LP. Prior Helicobacter pylori infection ameliorates Salmonella typhimurium-induced colitis: mucosal crosstalk between stomach and distal intestine. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011; 17(6):1398-408. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21489 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Väre PO, Heikius B, Silvennoinen JA, Karttunen R, Niemelä SE, Lehtola JK. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in inflammatory bowel disease: is Helicobacter pylori infection a protective factor?. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001; 36(12):1295-300. doi: 10.1080/003655201317097155 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg A, Genta RM. Low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012; 35(4):469-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04969.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Bazzoli F, Ford AC. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut 2018; 67(3):430-40. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Hasanpour AH, Eusebi LH, Ford AC. Systematic review with meta-analysis: association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastro-oesophageal reflux and its complications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021; 54(8):988-98. doi: 10.1111/apt.16585 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shavalipour A, Malekpour H, Dabiri H, Kazemian H, Zojaji H, Bahroudi M. Prevalence of cytotoxin-associated genes of Helicobacter pylori among Iranian GERD patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2017; 10(3):178-83. [ Google Scholar]

- Bor S, Kitapcioglu G, Kasap E. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in a country with a high occurrence of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(3):525-32. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i3.525 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Raghunath A, Hungin AP, Wooff D, Childs S. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: systematic review. BMJ 2003; 326(7392):737. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.737 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yucel O. Interactions between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Esophagus 2019; 16(1):52-62. doi: 10.1007/s10388-018-0637-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Waldum HL, Kleveland PM, Sørdal ØF. Helicobacter pylori and gastric acid: an intimate and reciprocal relationship. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2016; 9(6):836-44. doi: 10.1177/1756283x16663395 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mantero P, Matus GS, Corti RE, Cabanne AM, Zerbetto de Palma GG, Marchesi Olid L. Helicobacter pylori and corpus gastric pathology are associated with lower serum ghrelin. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(3):397-407. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i3.397 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Romo-González C, Mendoza E, Mera RM, Coria-Jiménez R, Chico-Aldama P, Gomez-Diaz R. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum leptin, obestatin, and ghrelin levels in Mexican schoolchildren. Pediatr Res 2017; 82(4):607-13. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.69 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias Á, von Arnim U, Bredenoord AJ, Bussmann C. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United European Gastroenterol J 2017; 5(3):335-58. doi: 10.1177/2050640616689525 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cheung KM, Oliver MR, Cameron DJ, Catto-Smith AG, Chow CW. Esophageal eosinophilia in children with dysphagia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2003; 37(4):498-503. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200310000-00018 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut 2007; 56(5):615-20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107714 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shah SC, Tepler A, Peek RM Jr, Colombel JF, Hirano I, Narula N. Association between Helicobacter pylori exposure and decreased odds of eosinophilic esophagitis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17(11):2185-98.e3. 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.013.

- von Arnim U, Wex T, Link A, Messerschmidt M, Venerito M, Miehlke S. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with a reduced risk of developing eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43(7):825-30. doi: 10.1111/apt.13560 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Molina-Infante J, Gutierrez-Junquera C, Savarino E, Penagini R, Modolell I, Bartolo O. Helicobacter pylori infection does not protect against eosinophilic esophagitis: results from a large multicenter case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(7):972-9. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0035-6 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018;154(2):319-32.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067.

- O’Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, Gupta SK, Spergel JM, Furuta GT. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154(2):333-45. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.065 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Environmental factors and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142(1):32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.015 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lv YP, Teng YS, Mao FY, Peng LS, Zhang JY, Cheng P. Helicobacter pylori-induced IL-33 modulates mast cell responses, benefits bacterial growth, and contributes to gastritis. Cell Death Dis 2018; 9(5):457. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0493-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Pesek RD, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease below the belt. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145(1):87-9.e1. 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.10.013.

- Park AM, Hagiwara S, Hsu DK, Liu FT, Yoshie O. Galectin-3 plays an important role in innate immunity to gastric infection by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun 2016; 84(4):1184-93. doi: 10.1128/iai.01299-15 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yazawa N, Fujimoto M, Kikuchi K, Kubo M, Ihn H, Sato S. High seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with esophageal involvement. J Rheumatol 1998; 25(4):650-3. [ Google Scholar]

- Cuomo P, Papaianni M, Capparelli R, Medaglia C. The role of formyl peptide receptors in permanent and low-grade inflammation: Helicobacter pylori infection as a model. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22(7):3706. doi: 10.3390/ijms22073706 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Davis CM, Hiremath G, Wiktorowicz JE, Soman KV, Straub C, Nance C. Proteomic analysis in esophageal eosinophilia reveals differential galectin-3 expression and S-nitrosylation. Digestion 2016; 93(4):288-99. doi: 10.1159/000444675 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Youngblood BA, Brock EC, Leung J, Falahati R, Bochner BS, Rasmussen HS. Siglec-8 antibody reduces eosinophils and mast cells in a transgenic mouse model of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. JCI Insight 2019; 4(19):e126219. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.126219 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cianferoni A, Spergel JM, Muir A. Recent advances in the pathological understanding of eosinophilic esophagitis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 9(12):1501-10. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.1094372 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ko E, Chehade M. Biological therapies for eosinophilic esophagitis: where do we stand?. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2018; 55(2):205-16. doi: 10.1007/s12016-018-8674-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Iwakura N, Fujiwara Y, Tanaka F, Tanigawa T, Yamagami H, Shiba M. Basophil infiltration in eosinophilic oesophagitis and proton pump inhibitor-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41(8):776-84. doi: 10.1111/apt.13141 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ayaki M, Manabe N, Nakamura J, Fujita M, Katsumata R, Haruma K. A retrospective study of the differences in the induction of regulatory T cells between adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dig Dis Sci 2022; 67(10):4742-8. doi: 10.1007/s10620-021-07355-x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Niyonsaba F, Kiatsurayanon C, Ogawa H. The role of human β-defensins in allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy 2016; 46(12):1522-30. doi: 10.1111/cea.12843 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lepe M, O’Connell D, Lombardo KA, Herzlinger M, Mangray S, Resnick MB. The inflammatory milieu of eosinophilic esophagitis: a contemporary review with emphasis in putative immunohistochemistry and serologic markers. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2018; 26(7):435-44. doi: 10.1097/pai.0000000000000450 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kountouras J, Deretzi G, Gavalas E, Zavos C, Polyzos SA, Kazakos E. A proposed role of human defensins in Helicobacter pylori-related neurodegenerative disorders. Med Hypotheses 2014; 82(3):368-73. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.12.025 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Attaran B, Falsafi T, Ghorbanmehr N. Effect of biofilm formation by clinical isolates of Helicobacter pylori on the efflux-mediated resistance to commonly used antibiotics. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(7):1163-70. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i7.1163 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tullie L, Kelay A, Bethell GS, Major C, Hall NJ. Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer following oesophageal atresia repair: a systematic review. BJS Open 2021; 5(4):zrab069. doi: 10.1093/bjsopen/zrab069 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Degiovani M, Ribas C, Czeczko NG, Parada AA, de Andrade Fronchetti J, Malafaia O. Is there a relation between Helicobacter pylori and intestinal metaplasia in short column epitelization up to 10 mm in the distal esophagus?. Arq Bras Cir Dig 2019; 32(4):e1480. doi: 10.1590/0102-672020190001e1480 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Israel DA, Peek RM Jr. Mechanisms of Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric inflammation. In: Said HM, ed. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 6th ed. Academic Press; 2018. p. 1517-45. 10.1016/b978-0-12-809954-4.00063-3.

- Nakashima H, Kawahira H, Kawachi H, Sakaki N. Endoscopic three-categorical diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection using linked color imaging and deep learning: a single-center prospective study (with video). Gastric Cancer 2020; 23(6):1033-40. doi: 10.1007/s10120-020-01077-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Li Y, Hu J, Wang X, Ren M, Lu G. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Dig Dis 2020; 38(4):261-8. doi: 10.1159/000504086 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ye W, Held M, Lagergren J, Engstrand L, Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy: risk of adenocarcinoma and squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96(5):388-96. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh057 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Iijima K, Koike T, Sekine H, Imatani A, Ohara S, Shimosegawa T. Gastric atrophy may be associated with the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus in Japan. Gastroenterology 2006; 130(4):A411. [ Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Lieberman D, Srinivasan S, Nutalapati V, Challa A, Kalgotra P. Post-endoscopy Barrett’s neoplasia after a negative index endoscopy: a systematic review and proposal for definitions and performance measures in endoscopy. Endoscopy 2022; 54(9):881-9. doi: 10.1055/a-1729-8066 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- ten Kate CA, de Klein A, de Graaf BM, Doukas M, Koivusalo A, Pakarinen MP. Intrinsic cellular susceptibility to Barrett’s esophagus in adults born with esophageal atresia. Cancers (Basel) 2022; 14(3):513. doi: 10.3390/cancers14030513 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- El-Omar EM, Oien K, El-Nujumi A, Gillen D, Wirz A, Dahill S. Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic gastric acid hyposecretion. Gastroenterology 1997; 113(1):15-24. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70075-1 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hojo M, Ueda K, Takeda T, Akazawa Y, Ueyama H, Shimada Y. The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and reflux esophagitis and the long-term effects of eradication of Helicobacter pylori on reflux esophagitis. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021; 14:17562848211059942. doi: 10.1177/17562848211059942 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Shiotani A, Graham DY. Current and future treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019; 1149:211-25. doi: 10.1007/5584_2019_367 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Jones AD, Bacon KD, Jobe BA, Sheppard BC, Deveney CW, Rutten MJ. Helicobacter pylori induces apoptosis in Barrett’s-derived esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. J Gastrointest Surg 2003; 7(1):68-76. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00129-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McColl KE, El-Omar EM, Gillen D. Alterations in gastric physiology in Helicobacter pylori infection: causes of different diseases or all epiphenomena?. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1997; 29(5):459-64. [ Google Scholar]

- Bahmanyar S, Zendehdel K, Nyrén O, Ye W. Risk of oesophageal cancer by histology among patients hospitalised for gastroduodenal ulcers. Gut 2007; 56(4):464-8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.109082 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li ZP, Liu JX, Lu LL, Wang LL, Xu L, Guo ZH. Overgrowth of Lactobacillus in gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2021; 13(9):1099-108. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v13.i9.1099 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Waldum HL, Rehfeld JF. Gastric cancer and gastrin: on the interaction of Helicobacter pylori gastritis and acid inhibitory induced hypergastrinemia. Scand J Gastroenterol 2019; 54(9):1118-23. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2019.1663446 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kunnumakkara AB, Harsha C, Banik K, Vikkurthi R, Sailo BL, Bordoloi D. Is curcumin bioavailability a problem in humans: lessons from clinical trials. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2019; 15(9):705-33. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2019.1650914 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori and oesophageal cancer--not always protective. Gut 2007; 56(4):457-9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111385 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Naylor GM, Gotoda T, Dixon M, Shimoda T, Gatta L, Owen R. Why does Japan have a high incidence of gastric cancer? Comparison of gastritis between UK and Japanese patients. Gut 2006; 55(11):1545-52. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.080358 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wu DC, Wu IC, Lee JM, Hsu HK, Kao EL, Chou SH. Helicobacter pylori infection: a protective factor for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a Taiwanese population. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100(3):588-93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40623.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Youssefi M, Tafaghodi M, Farsiani H, Ghazvini K, Keikha M. Helicobacter pylori infection and autoimmune diseases; Is there an association with systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune atrophy gastritis and autoimmune pancreatitis? A systematic review and meta-analysis study. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2021; 54(3):359-69. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.08.011 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Glatigny S, Bettelli E. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as animal models of multiple sclerosis (MS). Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018; 8(11):a028977. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028977 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Littman DR, Rudensky AY. Th17 and regulatory T cells in mediating and restraining inflammation. Cell 2010; 140(6):845-58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Codarri L, Gyülvészi G, Tosevski V, Hesske L, Fontana A, Magnenat L. RORγt drives production of the cytokine GM-CSF in helper T cells, which is essential for the effector phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol 2011; 12(6):560-7. doi: 10.1038/ni.2027 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Li W, Minohara M, Su JJ, Matsuoka T, Osoegawa M, Ishizu T. Helicobacter pylori infection is a potential protective factor against conventional multiple sclerosis in the Japanese population. J Neuroimmunol 2007; 184(1-2):227-31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ponsonby AL, Dwyer T, van der Mei I, Kemp A, Blizzard L, Taylor B. Asthma onset prior to multiple sclerosis and the contribution of sibling exposure in early life. Clin Exp Immunol 2006; 146(3):463-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03235.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Frieri M, Stampfl H. Systemic lupus erythematosus and atherosclerosis: review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2016; 15(1):16-21. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2015.08.007 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Fanouriakis A, Tziolos N, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. Update οn the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2021; 80(1):14-25. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218272 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi S, Iizumi T, Watanabe E, Shimizu M, Kamiya S, Nagata K. Implications for induction of autoimmunity via activation of B-1 cells by Helicobacter pylori urease. Infect Immun 2006; 74(1):248-56. doi: 10.1128/iai.74.1.248-256.2006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Sawalha AH, Schmid WR, Binder SR, Bacino DK, Harley JB. Association between systemic lupus erythematosus and Helicobacter pylori seronegativity. J Rheumatol 2004; 31(8):1546-50. [ Google Scholar]

- Hasni S, Ippolito A, Illei GG. Helicobacter pylori and autoimmune diseases. Oral Dis 2011; 17(7):621-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01796.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Shapira Y, Agmon-Levin N, Renaudineau Y, Porat-Katz BS, Barzilai O, Ram M. Serum markers of infections in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis: evidence of infection burden. Exp Mol Pathol 2012; 93(3):386-90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2012.09.012 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kalabay L, Fekete B, Czirják L, Horváth L, Daha MR, Veres A. Helicobacter pylori infection in connective tissue disorders is associated with high levels of antibodies to mycobacterial hsp65 but not to human hsp60. Helicobacter 2002; 7(4):250-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2002.00092.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Arnold IC, Müller A. Mechanisms of persistence, innate immune activation and immunomodulation by the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Curr Opin Microbiol 2020; 54:1-10. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2020.01.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010; 376(9746):1094-108. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60826-4 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa N, Fuchigami T, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi H, Sakai Y, Tabata H. Helicobacter pylori infection in rheumatoid arthritis: effect of drugs on prevalence and correlation with gastroduodenal lesions. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002; 41(1):72-7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.1.72 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Matsukawa Y, Asai Y, Kitamura N, Sawada S, Kurosaka H. Exacerbation of rheumatoid arthritis following Helicobacter pylori eradication: disruption of established oral tolerance against heat shock protein?. Med Hypotheses 2005; 64(1):41-3. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.06.021 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Steen KS, Lems WF, Visman IM, de Koning MH, van de Stadt RJ, Twisk JW. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on C-reactive protein and the lipid profile in patients with rheumatoid arthritis using chronic NSAIDs. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009; 27(1):170. [ Google Scholar]

- Janssen M, Dijkmans BA, van der Sluys FA, van der Wielen JG, Havenga K, Vandenbroucke JP. Upper gastrointestinal complaints and complications in chronic rheumatic patients in comparison with other chronic diseases. Br J Rheumatol 1992; 31(11):747-52. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.11.747 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Campochiaro C, Allanore Y. An update on targeted therapies in systemic sclerosis based on a systematic review from the last 3 years. Arthritis Res Ther 2021; 23(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02536-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Reinauer S, Goerz G, Ruzicka T, Susanto F, Humfeld S, Reinauer H. Helicobacter pylori in patients with systemic sclerosis: detection with the 13C-urea breath test and eradication. Acta Derm Venereol 1994; 74(5):361-3. doi: 10.2340/0001555574361363 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Iwakiri R, Hara M, Kikkawa A, Fujise T, Ootani H. Reflux esophagitis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with scleroderma. Intern Med 2008; 47(18):1555-9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1128 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Tumgor G, Agin M, Doran F, Cetiner S. Frequency of celiac disease in children with peptic ulcers. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63(10):2681-6. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5174-5 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Oertli M, Sundquist M, Hitzler I, Engler DB, Arnold IC, Reuter S. DC-derived IL-18 drives Treg differentiation, murine Helicobacter pylori-specific immune tolerance, and asthma protection. J Clin Invest 2012; 122(3):1082-96. doi: 10.1172/jci61029 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Arnold IC, Lee JY, Amieva MR, Roers A, Flavell RA, Sparwasser T. Tolerance rather than immunity protects from Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric preneoplasia. Gastroenterology 2011; 140(1):199-209. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.047 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Hmida NB, Ben Ahmed M, Moussa A, Rejeb MB, Said Y, Kourda N. Impaired control of effector T cells by regulatory T cells: a clue to loss of oral tolerance and autoimmunity in celiac disease?. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(4):604-11. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.397 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl B, Blaser MJ, Ludvigsson JF, Green PH, Rundle A, Sonnenberg A. Decreased risk of celiac disease in patients with Helicobacter pylori colonization. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178(12):1721-30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt234 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rothenbacher D, Blaser MJ, Bode G, Brenner H. Inverse relationship between gastric colonization of Helicobacter pylori and diarrheal illnesses in children: results of a population-based cross-sectional study. J Infect Dis 2000; 182(5):1446-9. doi: 10.1086/315887 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Longet S, Abautret-Daly A, Davitt CJH, McEntee CP, Aversa V, Rosa M. An oral alpha-galactosylceramide adjuvanted Helicobacter pylori vaccine induces protective IL-1R- and IL-17R-dependent Th1 responses. NPJ Vaccines 2019; 4:45. doi: 10.1038/s41541-019-0139-z [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Yaghoubi A, Khazaei M, Ghazvini K, Movaqar A, Avan A, Hasanian SM. Peptides with dual antimicrobial-anticancer activity derived from the N-terminal region of H pylori ribosomal protein L1 (RpL1). Int J Pept Res Ther 2021; 27(2):1057-67. doi: 10.1007/s10989-020-10150-3 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Bode G, Rothenbacher D, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori colonization and diarrhoeal illness: results of a population-based cross-sectional study in adults. Eur J Epidemiol 2001; 17(9):823-7. doi: 10.1023/a:1015618112695 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mattsson A, Lönroth H, Quiding-Järbrink M, Svennerholm AM. Induction of B cell responses in the stomach of Helicobacter pylori-infected subjects after oral cholera vaccination. J Clin Invest 1998; 102(1):51-6. doi: 10.1172/jci22 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi T, Nakayama A, Shimoda R, Matsuo M. Atrophic gastritis and chronic diarrhea due to Helicobacter pylori infection in early infancy: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98(47):e17986. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000017986 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Cover TL, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori in health and disease. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(6):1863-73. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.073 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Perry S, de Jong BC, Solnick JV, de la Luz Sanchez M, Yang S, Lin PL. Infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with protection against tuberculosis. PLoS One 2010; 5(1):e8804. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008804 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Inui A, Asakawa A, Bowers CY, Mantovani G, Laviano A, Meguid MM. Ghrelin, appetite, and gastric motility: the emerging role of the stomach as an endocrine organ. FASEB J 2004; 18(3):439-56. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0641rev [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Isomoto H, Nakazato M, Ueno H, Date Y, Nishi Y, Mukae H. Low plasma ghrelin levels in patients with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Am J Med 2004; 117(6):429-32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.030 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Osawa H, Nakazato M, Date Y, Kita H, Ohnishi H, Ueno H. Impaired production of gastric ghrelin in chronic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90(1):10-6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1330 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mori H, Suzuki H, Matsuzaki J, Kameyama K, Igarashi K, Masaoka T. Development of plasma ghrelin level as a novel marker for gastric mucosal atrophy after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Med 2022; 54(1):170-80. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2021.2024875 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Mera RM, Correa P, Fontham EE, Reina JC, Pradilla A, Alzate A. Effects of a new Helicobacter pylori infection on height and weight in Colombian children. Ann Epidemiol 2006; 16(5):347-51. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.08.002 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Roper J, Francois F, Shue PL, Mourad MS, Pei Z, Olivares de Perez AZ. Leptin and ghrelin in relation to Helicobacter pylori status in adult males. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93(6):2350-7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2057 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Suki M, Leibovici Weissman Y, Boltin D, Itskoviz D, Tsadok Perets T, Comaneshter D. Helicobacter pylori infection is positively associated with an increased BMI, irrespective of socioeconomic status and other confounders: a cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 30(2):143-8. doi: 10.1097/meg.0000000000001014 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]